We’ve written before about the dangers of Q-fever, and the urgent need for the Government to put more money towards detection, vaccination and prevention of this terrible illness.

Despite campaigning across the nation by our union, the health and well-being of meat workers (and all animal husbandry workers, because Q-fever doesn’t discriminate!), these calls have fallen on deaf ears. Australia may have a new Government, but nothing has changed for meat workers, who are still at risk.

Q-fever is a serious disease. The USA’s Centre for Disease Control lists it as a Class B bioterrorism agent, and the micro-organisms that cause the infection are incredibly hardy, surviving outside of the body for up to two months. If left untreated, it is almost always fatal.

Still the Government refuses to continue funding for this life-saving vaccination.

Now one of our members has reached out to tell us about how Q-fever has affected their life. Abattoir worker Hayley* recalls how her son was hit with what seemed like a normal flu, but quickly became so much more.

After a week of becoming progressively more and more ill from what doctors initially thought was just the flu, her son was checked into hospital. Blood tests and culture tests showed that he was having liver function problems. The infectious diseases department was called. Samples of his blood were sent off for urgent testing.

“I’ve never seen my kid that sick,” said Hayley. “I was devastated. He was so yellow. We had no idea what was going on.”

“It took so long for the test to come back, not knowing what was happening. It was devastating.”

The test did come back. The doctors confirmed that her son was suffering from Q-fever.

How did this happen?

Here’s the twist: In 2009, when Hayley’s son first entered the meat workforce, he was told by doctors that he didn’t need the Q-fever vaccine. His tests at the time returned results of what is called ‘pre-exposure’, where the result indicates that he had been infected in the past.

“I thought was very strange,” Hayley recalls. “I started work in June that same year, and I had the skin test — and I needed the vaccine. He’s my child and he’s been nowhere that I haven’t been, but you know, I guess I didn’t think much of it.”

Hayley didn’t want to argue with the doctors. She had no reason to suspect the test was wrong, or that the “ticking time bomb” of Q-fever was just waiting to send her child to hospital.

“My nephew and niece worked at the same place. My brother and sister, same situation. She got skin tests, but was told she didn’t need to get the vaccine. Another young fella I know in the shed was told he had prior exposure.”

“How long until this happens again?”

The long road home

After 11 days in hospital and seven weeks off work, Hayley’s son is finally getting ready to return to the abattoir, but it will be a long road until he’s back to his full strength.

“He’s not back to himself,” says Hayley. “Not at all. He’s fatigued. Not sleeping.”

“Other people in the industry have told me that next time he gets a bad flu it could flare up again.

Many employers in the meat industry have followed the Government’s lead and refuse to pay for, or even organise Q-fever tests and vaccinations. This hits international workers the hardest, many of whom don’t speak English and who are at the most risk if something goes wrong – with no family or support network to take care of them.

Hayley’s voice shakes as she tells us that more needs to be done, that the testing needs to be more accurate.

“It was scary. To know your child’s liver is failing, and just not knowing. Then discovering that it could all have been prevented!”

“I don’t want someone else to go through this.”

If you are experiencing any symptoms that you believe may be Q-fever related, contact your doctor immediately and notify the AMIEU.

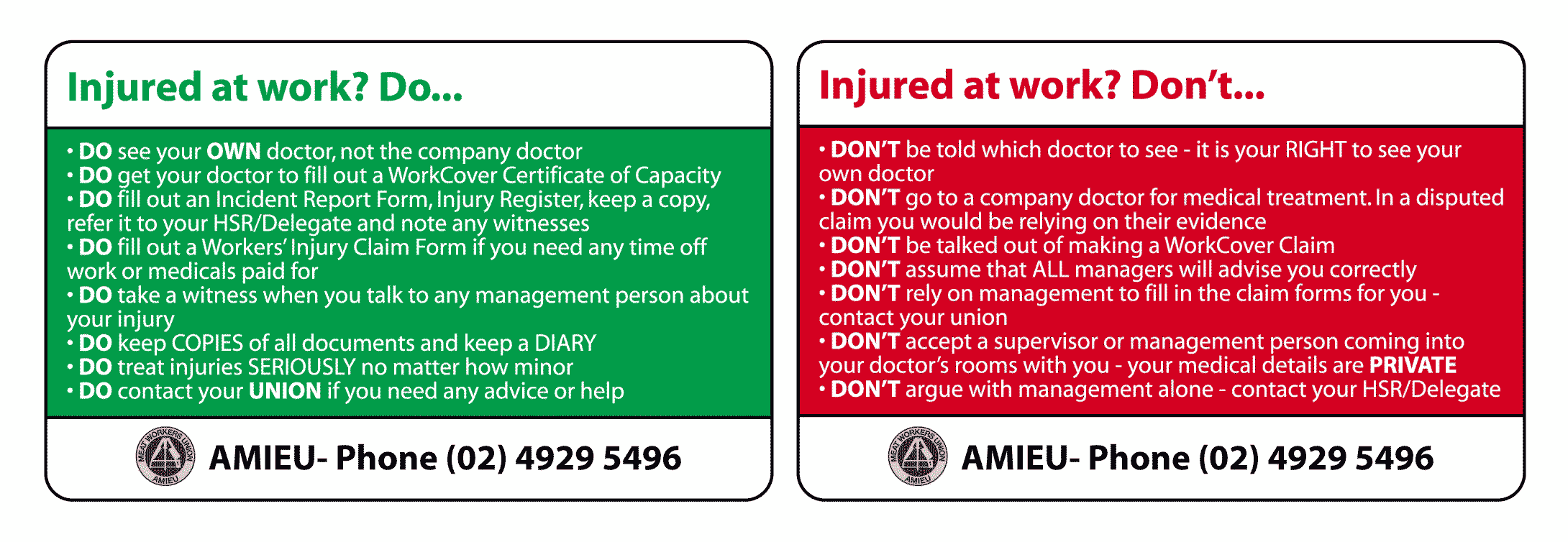

Remember to follow the AMIEU WHS Guide (below) at all times.

—

*Name changed at our member’s request